Q&A: Amali Tower on Climate Migration and 'Evolution Earth'

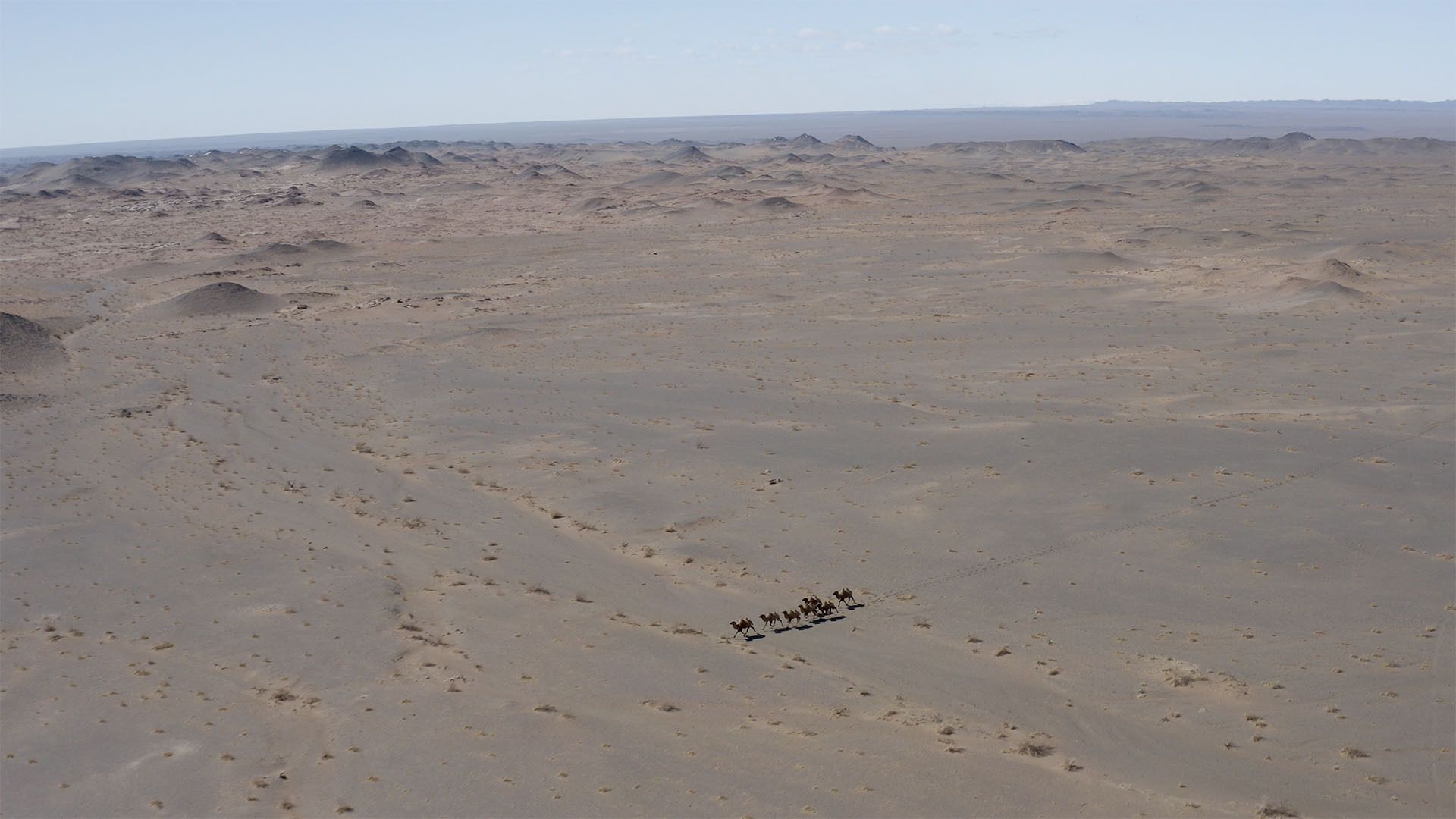

The Sahara is one of the largest deserts in the world and it only continues to grow. Expanding by 2,900 square miles a year, the desert’s growth impacts not only the wildlife but the people who live there — often forcing them to leave as it encroaches on their homes and creates unlivable conditions. In “Evolution Earth,” Founder and Executive Director of Climate Refugees, Amali Tower, took us to Morocco where she introduced us to the families who have experienced this firsthand.

PBS spoke with her to learn more about how climate change is affecting populations across the world, the growing refugee crisis, and climate displacement's impact on Indigenous knowledge.

What is climate migration?

Amali Tower: While there is no single agreed-upon definition, “climate migration” broadly refers to the movement of people either because of climate change effects (such as more frequent hurricanes or sea level rise making it impossible to remain in place) or for reasons that are exacerbated by climate change (such as when a prolonged drought diminishes livelihood and food security or worsens existing conflict to an extent that forces people elsewhere). While the term does not exclude voluntary migration in climate contexts, it is generally understood that climate migration is largely if not totally involuntary, as most people want - and will try pretty much everything - to remain where they are. Both slow (desertification, sea level rise, ocean acidification, etc.) and sudden onset (tropical storms, flash flooding, etc.) impacts drive climate migration, which can be either within a given country or across international borders.

What are the challenges facing climate refugees?

Amali Tower: Climate change is a factor in just about every case of forced displacement today - both within borders and across borders. Populations displaced across borders by climate change do not necessarily qualify as refugees as that status is reserved for people fleeing conflict and persecution across borders along political, racial and religious grounds, for example. People are displaced and forced to migrate for a variety of reasons: insecurity of all kinds from conflict to economic distress, and in almost all cases, climate change is a complex and intersecting factor driving and increasing the need to move.

In recent years, climate change has displaced more people within their countries than even conflict or violence. And while most climate displacement is happening internally, it is developing countries that are frontline to the climate crisis, though they have contributed very little to creating the problem. That means climate change is having devastating impacts on people in the Global South, displacing poor urban communities who live in informal settlements when weather extremes lead to increased and more intense disasters. Climate change is also forcing rural communities to have to move in search of better livelihoods when scorching temperatures and decreased rainfall force drought, crop and livelihood loss upon millions of people who are wholly dependent on the land and natural resources for survival.

One of the biggest challenges for climate migrants is the ad-hoc patchwork of international protection mechanisms that may cover some but not others. For example, for people displaced by climate change within their countries, their protection is very clearly the responsibility of their government. But this becomes an increasing burden for governments in poor countries who have the responsibility of caring for their own internally displaced citizens, as well as hosting migrants from neighboring countries. For those displaced across borders in the context of climate change, things are a lot more complicated because the Refugee Convention does not afford refugee protection on the basis of climate change or environmental degradation. And while the UN Refugee Agency has published guidance on how the Convention can apply in certain climate change contexts, the vast majority of those displaced across borders by climate change lack adequate international protection. This means they are at particular risk of having their rights violated, and of accessing durable solutions like resettlement.

What regions and populations are most at risk of climate displacement?

Amali Tower: As no region is untouched by climate change, climate displacement can occur anywhere. But the majority of this displacement occurs in the Global South, generally in countries that are the least responsible for climate change if you look at historical cumulative emissions. Entrenched poverty, economic reliance on the environment, legacies of colonialism and debt burdens are just some of the factors that are exacerbated by climate change impacts. And so while the US and Western Europe can afford to prepare for sea level rise and to rebuild fairly easily and quickly following wildfires and severe flooding events, countries in the Global South simply don’t have the means to adapt in the same way and therefore are at much higher risk of experiencing climate displacement. Within any country, but especially those in the Global South, risk of displacement is amplified for marginalized communities who are often forgotten or deprioritized when governments map out their adaptation and disaster-response strategies. These people may also simply lack the means to migrate and therefore become trapped in place, with very troubling implications in terms of rights and protection.

Pacific island states are particularly vulnerable right now to rising sea levels, where some island states have already lost land, saltwater intrusion in their soil affects not only food security, but trade and entire cultural ways of life going back millennia. Asia, in particular South East Asia, is dealing with increasing climate disasters. Bangladesh is a good example. The drought and increased disasters in Central America’s Dry Corridor are additional factors pushing populations to the US southern border. The boats carrying thousands of people from Africa, Asia and the Middle East across Europe’s Mediterranean waters are also fleeing devastating climate impacts from the Sahel to Pakistan, and many places in between.

In "Evolution Earth," you visit Morocco and speak to individuals who have been impacted by desertification. What are some other examples of climate migration happening today and where else in the world are we seeing this?

Amali Tower: Unfortunately, climate migration has been occurring for some time, and no region is unaffected. To better understand the specific ways people are affected and the intersecting nature of climate change, it’s incredibly important that we speak to affected communities. Last year I spent a good deal of time in Kenya doing exactly this. Through visiting communities, I heard from Indigenous and pastoralist communities in the Rift Valley that they are being displaced by both historic drought and lake-level rise caused by higher-than-normal rainfall. In some cases, these climate impacts are directly displacing people, such as when homes and even entire communities are submerged. In other cases, climate impacts exacerbate existing conflicts over scarce resources, causing households to move elsewhere in order to feed their families. And where people are not yet displaced, they are suffering horrific losses. For instance, young children - mostly girls - who once went to school, are now foregoing their education to walk increasingly longer distances in search of water. Entire communities are having to get involved in digging deeper water holes as water tables start drying up. Some of these water holes have even collapsed, killing a number of people within them. Today, the flooding that has ended the drought, has displaced over a million people across Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania.

While Africa and Asia are particularly impacted by climate migration, we are also seeing it in the Americas, like in Central America’s Dry Corridor. I have spoken to migrants along the US southern border who have told me that prolonged drought, scorching temperatures, increasingly frequent tropical storms, and sporadic rainfall are pushing many to make the dangerous journey north towards the US.

The best of PBS, straight to your inbox.

Be the first to know about what to watch, exclusive previews, and updates from PBS.

How will climate migration impact countries like the U.S.?

Amali Tower: Climate migration is already affecting the US in various ways. Increasingly severe and frequent wildfires, hurricanes, droughts, and other climate impacts are causing internal displacement. Those who can afford to move are doing so, for example, leaving the wildfires in California behind for safer grounds in Vermont. And while climate-driven displacement is generally short-term for most, some are displaced for years, usually marginalized, poor, immigrant and communities of color. Immigrants and undocumented populations in the US are particularly vulnerable in climate disasters as their living conditions tend to adversely impact them but fear of reprisals and deportation have prevented many from seeking assistance.

Climate disasters are also very costly. With hundreds of billions of dollars in losses from climate disasters annually, the US has seen a significant uptick in the number of high-cost disasters in the last few decades, a trend that stretches both public and private budgets and leaves residents vulnerable. For example, I’ve visited historically underserved and marginalized black and immigrant communities in Miami, where I learned that in Florida, several insurance companies have pulled out of the state in recent years, in part because of the high risk of climate disasters. Flood insurance premiums based on FEMA assessments have led some homeowners’ premiums to skyrocket in some places, forcing some who can afford it, to move, while others find they have no choice but to forego insurance. For residents who already struggle to pay their premiums, a gap in coverage - or being dropped from a policy altogether - can have devastating consequences when the next disaster strikes, including being unable to rebuild or return to their community. At the same time, climate impacts elsewhere, like drought and hurricanes in Central America, Haiti and the Western Caribbean, will continue to drive migration to the US despite US government attempts at deterrence, putting migrants in danger and straining an already overwhelmed immigration system.

Watch Evolution Earth

In the series you touch on cultural loss from climate change. Can you tell us more about this?

Amali Tower: Years of interviewing displaced people has taught me that to be displaced is to lose not just one’s home, possessions and livelihood, but also one’s community and the cultural ties that bind, enriching life and giving it meaning. That cultural loss is seen in all that is not passed on from generation to generation, the erosion of culture and community cohesion. For example, displacement disturbs the passing of knowledge and traditions - Indigenous and historical farming practices, traditional knowledge and more that is usually passed on orally and through lived experience to each generation.

And for others, cultural loss is the loss of cultural heritage and significant sites, like the Indigenous Endorois People in Kenya who, because of flooding, have lost access to the burial sites of their ancestors. For the Endorois, visiting their ancestors' burial grounds on a regular basis is a sacred act, one which has now been stripped from them due to climate change.

Support your local PBS station in our mission to inspire, enrich, and educate.

How will climate migration evolve over the coming decades?

Amali Tower: In 2023, 114 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide due to conflict, persecution, poverty and climate-related disasters. At least 60 percent of those displaced live in countries that are most vulnerable to climate change. Every year displacement numbers rise. So too does the Earth’s temperature.

While there are many projections on climate migration that anticipate hundreds of millions of people being forced to move by 2050, we don’t actually know how many will be displaced. Even more, many still lack adequate protection. But because climate emissions are not reducing fast enough, we can be sure that displacement will continue to rise. So polluting countries should realize that what is happening today is largely forced migration because of their inaction on climate mitigation and climate adaptation. It’s so important we realize that nobody wants to be forced to leave their home. But in the absence of adequate climate adaptation, we have not supported the right to stay.

What can people and organizations do now to help climate refugees?

Amali Tower: The action needed is really two-fold. On one hand, we must push our elected officials to take bolder climate action, both in terms of reducing emissions and scaling up adaptation efforts, both at home and abroad. This is the only way to curb climate change impacts and the displacement that arises as a result. At the same time, we should also advocate for better and expanded protections for people who are displaced, because this is already happening to millions around the world. Expanded social protection for those displaced internally would go a long way to reducing disruptions to livelihoods and education. For those displaced across borders by climate change, existing regional agreements as seen in some regions of Africa, can be models for expanded protection, but it is also time to consider international cooperation and expanded rights that can help the millions on the move who are not being afforded enough legal protection.

Each year, the number of people globally displaced rises, and increasingly, climate change is a major contributor to most displacements. Solutions require global cooperation to immediately lower emissions, help communities adapt to the forces of climate change, including supporting and resettling those who are forced to move, and finding remedies and compensation for communities who have suffered adverse losses and damages. These solutions are only possible with adequate political will, so voters and civil society have a major role to play in whether they come to pass.

How do you stay optimistic about our climate future?

Amali Tower: It’s not easy at all to stay optimistic, and sometimes I simply fail at that. But luckily, I have learned a great deal from displaced populations - chiefly their immense resilience in the face of insurmountable odds. For many, this resilience is enforced. Enforced upon them because they have no choice but to find solutions to the growing and interconnected problems they face every day. Within these solutions lie examples that must be shared, replicated and taught to many who can benefit, including policymakers who simply do not understand the scale and humanity of the climate problem. To do this, I’m a firm believer in storytelling. Storytelling that comes from the communities themselves. Stories that they must tell. That we must uplift and be intentional in placing for everyone to see. The problems we face when it comes to climate displacement, or even just climate change in general, can seem insurmountable at first glance. But a closer inspection reveals that a lot of progress has been made in a relatively short period of time. If we can harness that opportunity with the resilience of frontline communities, I think there will be a lot more optimism to go around.