Imagine your hometown could speak. What stories would it tell about the people who shaped it?

If you live in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Los Angeles, you’ve probably heard a tale or two about the Great Migration. It’s a story that spans two world wars, with themes of opportunity, determination and fortitude.

The Great Migration was a historic movement of Black Americans, primarily in response to rampant injustice and racial violence. From around 1910 to 1970, these communities left their southern homes to look for better lives in the Northeast and West. It was a journey that echoed American and African-American history, but it didn’t stay in the past; it also reshaped the narrative of our future.

“Great Migrations: A People on the Move” is a four-part docuseries hosted by award-winning filmmaker and scholar Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. exploring the people and places that made this movement monumental. You’ll learn the “what, why, when and where” — so let’s take a look at how it all came together to shape the story of America.

The When: Timeline of the Great Migration

Because the story of the Great Migration has so many moving parts, it’s often broken into phases to organize its main events. Let’s take a closer look:

The First Great Migration (approx. 1910-1930)

Beginning: The Civil War ended in 1865, but the first wave of the Great Migration didn’t start until after several waves of movement within the South.

- Key events:

#1: WWI ran between 1914 and 1918, creating new job opportunities in the early days of this first phase.

#2: The Great Depression began in 1929, overlapping with the Great Migration by one year, and ended in 1939.

Main cities: Most migrants went to northern cities, including Chicago, Detroit and Pittsburgh.

Main challenges: Racism took different forms in the North, leaving Black Southerners to learn a new set of unspoken expectations and prejudices.

Statistics: According to the National Archives, an estimated 2 million people moved during this phase.

End: The first year of the Great Depression eliminated many opportunities to move and prosper across the country.

The Second Great Migration (approx. 1940-1970)

Beginning: War efforts kickstarted the economy and the second wave of Black migration.

- Key events:

#1: WWII began in 1939, laying the groundwork for new job opportunities, and ended in 1945.

#2: The beginnings of the March on Washington movement in 1941, which wouldn’t culminate in an actual march until 1963, helped improve racial equality in hiring practices during the war’s early days.

Main cities: Black migrants still went to cities like Detroit, but this time, they also moved to Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle and Portland.

Main challenges: Overcrowding was a top concern during the second wave, on top of increasing racial pressure alongside the growing Civil Rights Movement.

Statistics: The second migration involved 4.5 million people moving across the country. By this point, according to Smithsonian Magazine, 47% of all African Americans lived in the North and West.

- End: Migration began to slow in the late 1960s and eventually “reversed” around 1970 as Black Americans followed job opportunities, family roots, familiar morals and a little bit of nostalgia back home.

Read on for a more detailed look at the causes and results of the Great Migration.

The What and Why: Defining the Great Migration

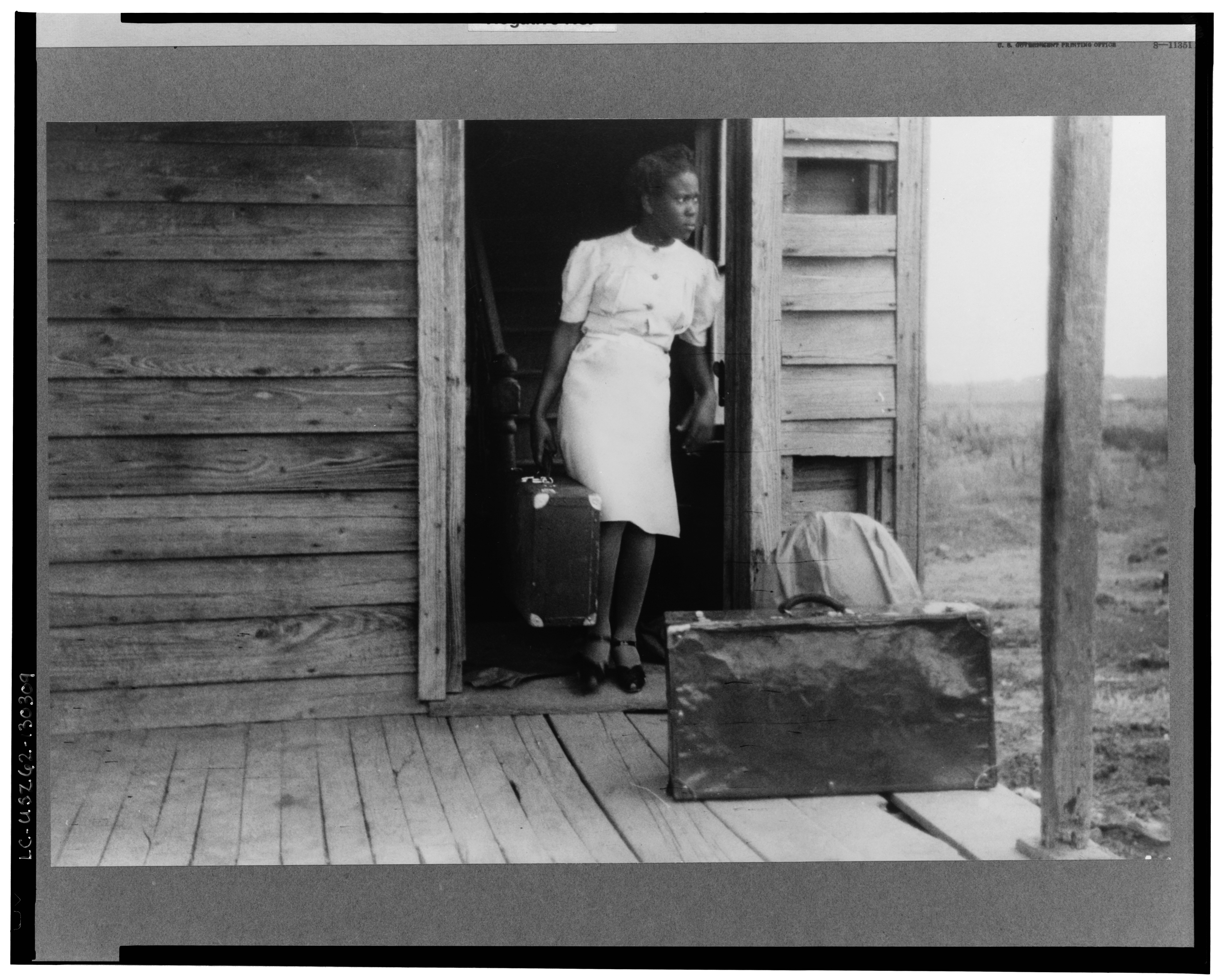

As you’ll learn in “Great Migrations,” the end of the war marked a moment of movement. Parents sought to reunite with children who had been sold away. Families looked for safer places to call home. People with the freedom and right to earn their own money were searching for paying work. It was a time of constant motion — but for the most part, it happened within the South.

In fact, 90% of Black Americans lived in the South after the Civil War. Many chose to stay, hoping that emancipation would pave the way for a new future in an old home. Even as that promise began to come apart at the seams throughout the 1870s, people stayed where the dialect, food and weather were familiar, thinking new beginnings were out of reach.

Still, staying in the South meant living through racially-motivated violence. According to Smithsonian Magazine, African Americans were being lynched more than once a week starting around 1880. With racial violence on the rise, Black Southerners had to decide whether to stay and fight for political power or would they vote with their feet and say goodbye to the only home they’d ever known. Once again, war decided for them.

The PBS 'Black Culture Connection' Newsletter

Celebrate Black history all year round with PBS Black Culture Connection. We'll connect you with films, timely discussions, live events and educational resources.

The Beginning of Black Migration

By 1914, with World War I raging across the sea, Black Americans were joining the fight in more ways than one. Some went to the battlefield, creating more proof for what never should have needed proving: Black people were worthy of their citizenship and, more importantly, their humanity.

Meanwhile, on the homefront, European immigration was declining. Companies in Northern cities needed new workers — an increasing demand that sparked the tinder of the Great Migration. It wasn’t just an economic opportunity; it was an active utilization of hard-won freedom, a chance to leave the inhospitable South on one’s own terms instead of in a desperate escape. This meant that Black migrants were looking for more than jobs as they headed up the map.

For many southern African Americans, Chicago was the Promised Land. According to The History Channel, Chicago’s Black population grew by 148% between 1910 and 1920. It had Black-owned businesses, Black men on baseball teams, independent Black filmmaking and artistic influences from Black communities across the nation — all things the South hardly dreamed of, let alone welcomed. And Chicago wasn’t alone: Black populations increased in New York City (66%), Philadelphia (500%) and Detroit (611%), too.

Of course, these cities weren’t perfect. As you’ll learn in “Great Migrations,” Black migrants felt that they’d walked into a tangled trap of unwritten rules, codes and limitations — injustices that had at least been visible in the South. Now, they were left learning how to exist in a world that — despite asking them to uproot their lives and then benefitting from their labor — still refused to treat them equally.

The Harlem Renaissance

When World War I ended, everything from country-wide racial relations to everyday life only got worse. With concerns about lost job opportunities, tensions rose and eventually exploded, leading to a year full of racial violence. 1919 saw incidents in 26 cities across the nation, earning the name “Red Summer” as Black families protected the new communities they’d worked so hard to build.

Out of the ashes came a new identity built on resistance, determination and the transformative energy of migration. Writer and philosopher Alain Locke called it “the new Negro” in 1925, but the movement it created would earn a different title when it found its home in Harlem.

Here, a culture of creativity and self-expression came to life in a new kind of renaissance. People like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay were weaving the spirit of the movement into art, telling stories unique to the culture but meaningful to all. African American migration had a voice — and it was heard throughout Harlem.

Just as importantly, it was heard at the voting booth.

The Harlem Renaissance gave Black people an opportunity to share, discover and develop new ideas about their values and power. They brought that sense of identity into their voting decisions, turning the tide of a government that had been all white for nearly 30 years. By 1928, Congress had its first Black representative in the 20th century: Oscar De Priest, who was born in Alabama and spent 20 years building a political career in Chicago. Unfortunately, with the Great Depression creeping around the corner in 1929, migration — and the progress it brought — was about to change again.

A Second Wave

When once-rich fields turned to dust and hungry hands had nothing to harvest, opportunity seemed like a distant memory. Black Americans in both the North and South were the most affected, with unemployment over 50% — they were often the last hired and the first fired. Even when World War II broke out in 1939, the job boom didn’t reach the African American population until somebody took a stand.

That somebody was A. Phillip Randolph, president of the first Black labor union and organizer of what would become the March on Washington. The first march, planned for July 1941, was called off when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order intended to ensure racial equality and better hiring practices in the defense sector.

Inspired by this new opportunity, Black Americans went on the move again. This time, they left the South and followed the job market to the West, settling mainly in Southern California. What happened in Harlem happened in Los Angeles: A vibrant identity grew around Black residents carving out their own culture.

However, with over 100,000 African American migrants landing in LA in the 1940s, overpopulation became a serious problem. People crossed unofficial, invisible borders between Black and white neighborhoods, causing chaos on both sides.

When World War II ended in 1945, previous generations of migrants had finally built a stable foundation for upward mobility. Thanks to legal battles, union movements and a refusal to accept the limitations of discrimination and segregation, these communities had created opportunities for themselves. This progress even echoed back home, where remaining Black Southerners were inspired to demand better from their economies and communities.

The Great Migration Today

The Great Migration slowed down and eventually reversed in the 1970s, with Black Americans heading back South to cities like Atlanta. No matter where they ended up, these migrants and their predecessors undeniably set the stage for Black popular culture, the Civil Rights Movement and the future of America.

Today, the legacy of the Great Migration lives on in the people and places it reshaped. Its impact ranges from the personal and intimate, like the family stories you’ll hear in “Great Migrations,” to the vast and cultural, like the story of a boy who went mute for eight years after his migration experiences only to become the voice of Darth Vader later in life. Even if you don’t have a personal connection to the Great Migration, it’s likely shaped your experiences, too — all because brave Americans demanded better and were willing to shape the future with their own hands.

Learn More About the Great Migration

The face of America changed with every footstep in the Great Migration. It was a tapestry of individual stories and shared experiences — a movement both literal and figurative. Perhaps most importantly, it turned the injustices of the past into the opportunities of the future, giving Black Americans a chance to pick up the pen and take charge of their own narrative.

But the Great Migration is more than just a timeline of important events. It’s a part of American history woven into our art, culture and society — and you can see it all for yourself.

Start watching “Great Migrations: A People on the Move” on PBS today!