Nakamura and Boch Reflect on 'Atomic Cafe: The Noisiest Corner in J-Town'

Did you know that a mom-and-pop diner in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of LA was a hub for the 1970s and 80s punk scene? On any given night, it wasn’t unusual to find women in kimonos sitting next to musicians with spiked hair. One of two films entered by the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) into this year’s PBS Short Film Festival, the short documentary "Atomic Cafe: The Noisiest Corner in J-Town" dives into how this Japanese American restaurant and its colorful proprietor, “Atomic Nancy,” influenced punk music.

We talked with directors Tad Nakamura ("Mele Murals," "Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings") and Akira Boch ("The Crumbles," Emmy-award winning "Masters of Modern Design") about the deep roots of this institution in the Japanese American community of southern California and the process of making this film.

Grace Hwang Lynch: You have both been involved with Los Angeles Little Tokyo for a long time, so could you start off by telling us a little about how the Atomic Cafe figures in the community lore, or even your own memories or family stories?

Tad Nakamura: My earliest memory is actually in context of Atomic Nancy’s singing ability, not the Atomic Cafe. Growing up I would hear my parents talk about this “Atomic Nancy” and how she had such a powerful voice when she sang with the group Hiroshima, one of the most famous Japanese American bands. Once I learned that she got her nickname from the Atomic Cafe I began hearing all these stories about the wild times people had there.

Most community members of that generation either partied there themselves, were envious that they weren’t able to, or were told by their parents to never go there. It definitely has a legend of it’s own but more in a super local, or underground sense. It really provided a space for so-called “outcasts” and “misfits” that felt they didn’t belong or were not accepted by the broader community and society. I think the reason why the Atomic Cafe is so legendary is that it created a space that was so different than any place in Little Tokyo at that time. From a business and community perspective, it was really brave of Nancy to be so unapologetic of who she was and what she wanted the Atomic Cafe to be.

Grace: Atomic Nancy sounds like an amazing woman! The Atomic Cafe was a fixture not just for the local community or LA music scene, but an influential space for punk music overall, which is often represented as white, male, possibly British. Why was it important to you to tell this story from a Japanese American perspective?

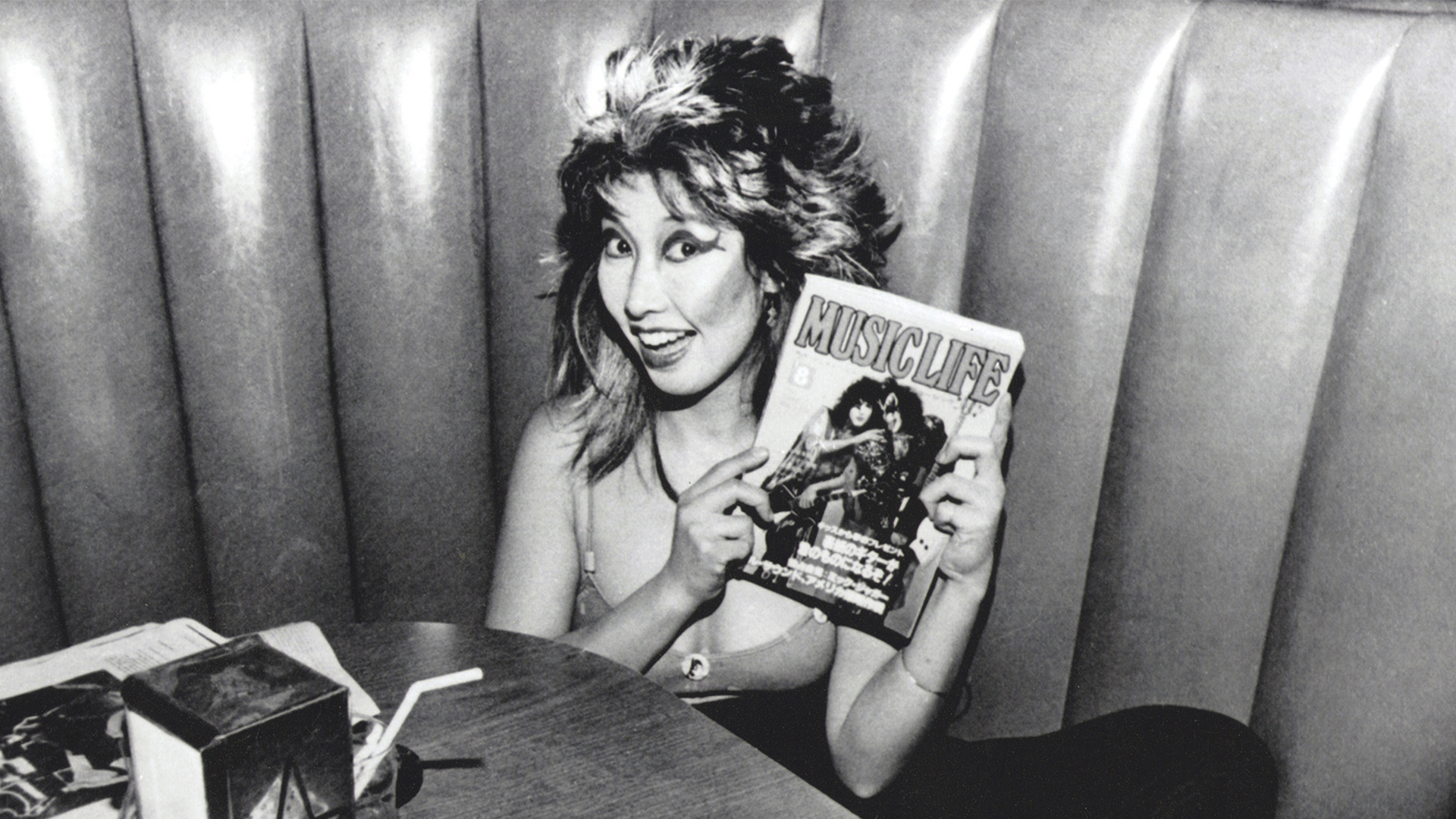

Akira Boch: Atomic Nancy is at the center of this story, so it was natural to tell it from her perspective, which is distinctly — and proudly — Japanese American. Her cafe was located at an important intersection in LA, where Little Tokyo, Boyle Heights/East LA, and the Arts District meet, which means that her clientele was coming from a diverse range of neighborhoods. Many of the punk shows happened in Chinatown, which was only a few minutes away. So if you look closely at the photos of LA’s punk music scene in the late 70s and early 80s, you’ll see that people of color were present and actively making that culture alongside the white kids. In my view, they were rallying around the themes of rebellion and alienation more than anything else, which people from any background can relate to. And Atomic Nancy was consciously providing a home base for all the young misfits and outsiders who needed a place to feel welcome and accepted.

Grace: Luckily, there were a lot of great photos of Atomic Nancy and some of the other celebrities who frequented the Atomic Cafe. What were the challenges of producing a documentary about a restaurant that closed its doors in 1989 and whose building has since been demolished?

Akira: The main challenge was obtaining enough visual material to convey the story, and then altering and playing with that material so it fit the vibe and aesthetic of the Atomic Cafe. Atomic Nancy and her daughter Zen had lots of great family photos and other images taken by professional photographers back in the day. But I have a feeling that there are many other photos out there of the Atomic that we didn’t come across.

Grace: If you’re in Los Angeles, can you see any traces of the Atomic Cafe today?

Akira: The Atomic’s neon sign is part of the permanent exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum, if anyone wants to see it in person. The building that housed the Atomic Cafe was demolished in order to make way for a major light rail hub, which is going to connect Los Angeles from all directions. So, kind of ironically, the location will continue to act as an intersection for many different communities.

Grace: How can people learn more about the Atomic Cafe or find out more about your work?

Tad: There is actually a really great kids series on Netflix called "City of Ghosts" that profiles different neighborhoods in LA. The episode “Bob and Nancy” actually features Atomic Nancy, Zen, and the Atomic Cafe. Zen is also a photographer and filmmaker and is working on a larger project about her family centered around the Atomic Cafe.

Most of my other work can be found on my website, and you can follow me @tadashinakamurafilms on Instagram or tad.nakamura on Facebook.

Akira: My website is Akira Boch, and I am @akira.boch on Instagram and akira1 on Facebook.

“Atomic Cafe” will be streaming on PBS.org from July 12-23 as part of the PBS Short Film Festival 2021.

Atomic Café

About the Author

More like this

Visit the Behind The Lens Blog