Dogs Behind Bars: Filming the 'Happy Hounds' Prison Dog Program

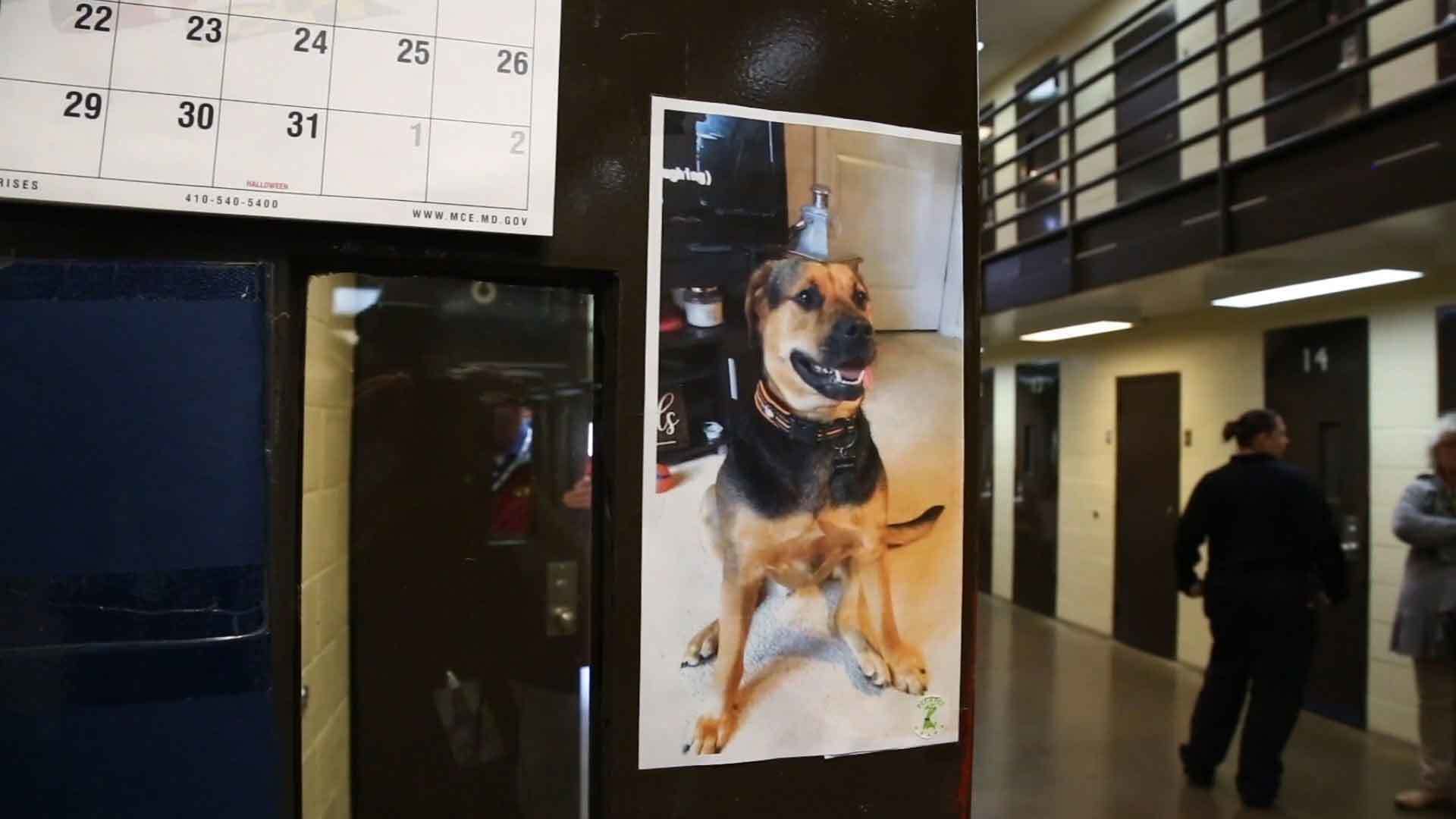

At the current historical moment, a critical eye is being cast toward the criminal justice system in the United States on an international level. Against this backdrop, a look into the lives of incarcerated people may be of greater importance than ever. A variety of educational and emotional programs for incarcerated populations exist, but what do they look like on the ground? "Happy Hounds" is a short documentary about a Maryland-based program that pairs inmates with dogs in need of rehabilitation.

MPT: What sparked your interest in telling this story? How did you hear about Linda Domer and the Happy Hounds Program?

Amy Oden: I have been interested in covering prison reform for a number of years, especially after filming with Reproductive Justice Inside and Life After Release, as they helped pass bills in Annapolis on incarcerated women’s hygiene and reproductive health.

A member of the executive team at Maryland Public Television actually met some of the gentlemen enrolled in the Happy Hounds program when he toured the facility at Roxbury Correctional Institution, and he put me in touch with the Maryland Department of Corrections, who handed me off to Linda.

Happy Hounds, by the way, was the name the inmates chose for their program, so I thought it was fitting to boost that in the title for the piece!

MPT: What was the process of filming in a prison like?

Amy: I had a meeting with the Maryland Department of Corrections and met a bunch of people on their team before they could issue approval for me to film. Since MPT is a state agency, it wasn’t actually as difficult as I thought it might be to get approved, but the DOC coordinated everything that would happen when I went to the cell block.

I started my production days by just doing a ride-along with Linda. I wanted to spend time with her before turning a camera on her, and it was pretty wild to see how much driving a dog trainer does in a day. She’s constantly taking dogs for appointments, picking up new animals, and doing evaluations - all over the state, and beyond.

We went into the prison on day two of production. The DOC media relations folks met us, but the tower guards still seemed hesitant to let us in the gate, as I had a camera. All the equipment had to be combed over and identified on a list. Filming in a carceral setting is not “normal.”

Once I arrived on the cell block, I met the inmates who were appointed to be on camera. Since Roxbury is a state penitentiary, no one’s sentence is less than 18 months. Many of the men there have been convicted of crimes that involve survivors, and the DOC has to reach out and obtain permission for them to be shown on film. These restrictions meant that I couldn’t film anyone’s face except the two men who had been designated as interviewees.

I’m used to being alone with the people I film, so it was strange to me that there were people nearby while I was interviewing, since the men were obviously nervous. One told me he hadn’t slept the night before. I’m also used to shouldering the emotional labor of talking people down during interviews if they get anxious, but his reaction was definitely more severe than that of most people I’ve worked with. We spent a lot of time diffusing tension and taking breathers when needed. Years prior, one of the women from Life After Release had told me that returning citizens need to be treated gently. Her words definitely echoed in my head during the process.

Once the interviews were over, it was a mix of loosely-structured lessons and drills for the dogs, while Linda did her weekly evaluations. Filming with the dogs was a frustrating but familiar experience; animals can be tough on camera, and my time was limited to what the DOC folks would allow.

Luckily the weather held, and I was able to get everything I needed in one full day on the cell block.

MPT: How did the story evolve?

Amy: Linda mentioned Jonathan to me a few times while I was with her during the aforementioned shoot days, and again during our “sit-down” interview at her house. I typically like to do interviews first, but because of her tight schedule, and needing to block off time to go to the prison, I had to be flexible about my own workflow.

Jonathan seemed, to me, to present an interesting postscript to the story, so I decided to follow her lead and contact him, which led to two more days of shooting in Waldorf, Maryland. I’ve said many times that filmmaking requires a mix of planning and flexibility, and this project was not unusual in that respect. I was glad to be able to demonstrate that the Happy Hounds program can forge a potential path to employment after release.

MPT: What is the intended message of the piece?

Amy: I think it’s important to look at the lives of people who are incarcerated, even as we try to chip away at what’s wrong with the criminal justice system. There’s a lot of work to be done, on all sides. Folks looking for a more comprehensive systemic examination should check out "13TH" and "When They See Us."

MPT: What else are you working on now?

Amy: I have another short documentary called "Lipstick and Leather," about alternative drag, that’s starting a run in some festivals in South and Central America. My independent work is here [on my website]. I’m also always producing for Maryland Public Television, and that’s featured on our website.

Happy Hounds

About the Author

More like this

Visit the Behind The Lens Blog