Gladiators, Theater & Ancient Roman Entertainment

In our modern-day world, we’re constantly inundated with different entertainment mediums – whether it’s a flashy Instagram post on your feed or the latest star-studded blockbuster to hit the theaters, there are endless outlets to satisfy your dopamine levels.

Travel back a couple thousands of centuries earlier to ancient Rome, and you’d also find that the Romans had a knack for staying entertained… albeit with a slightly more violent edge. Over at the Circus Maximus in Rome, you could discover charioteers chasing for first place in high-speed races, or in the Colosseum, flocks of people would gather to watch undaunted gladiators spar in menacing battles.

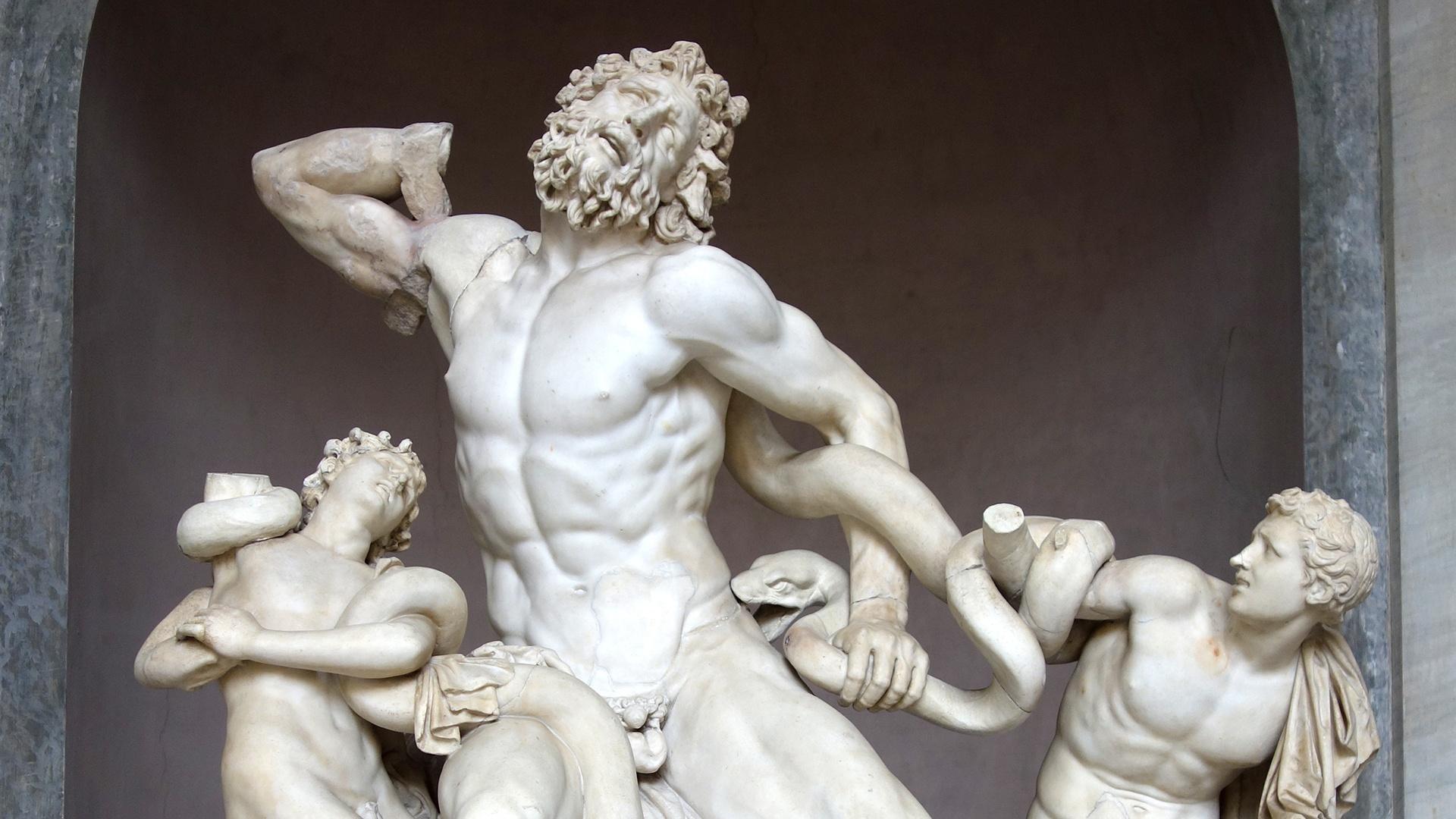

So where did the Romans acquire such a fascination with sport and spectacle? Turns out, they took a lot of inspiration from the Greeks who were distinguished for their athletics, a fact that was put on display at the first Olympic games in 776 BCE. While the Romans did not carry on the Greek Olympic tradition, they adopted their own styles and influences to these sports and even created some of their own.

Read on to learn about the violent gladiatorial fights and Roman games as well as Roman theater and other forms of entertainment.

Gladiators

Who Were Gladiators?

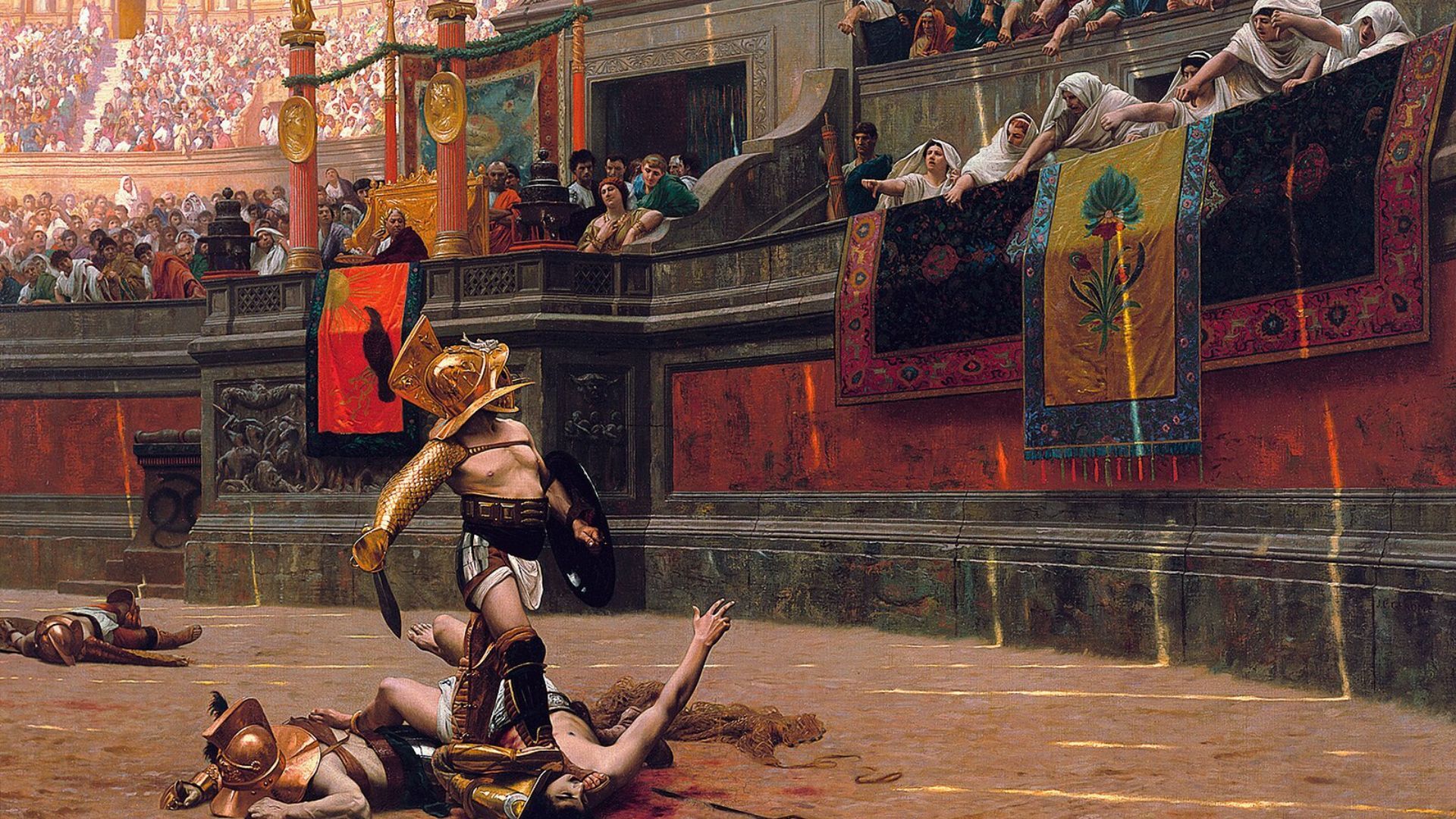

Gladiators were trained combatants who fought in public spectacles during the time of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. Contrary to popular belief, not all gladiators were enslaved people, although the majority of them tended to be. Convicted criminals would enter gladiator training, and records also suggest that some freed citizens volunteered to become gladiators, however, this was not as common. Even emperors could fight as gladiators, as was the case with the infamous Emperor Commodus who was portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix in the 2000 blockbuster film, Gladiator.

How To Become a Gladiator

Not anyone could sign up to be a gladiator: as with most fighting disciplines, a gladiator required extensive training. Gladiators would attend demanding, militaristic training camps called ludi. Within Rome, there were four schools to enroll in, with one of the most notable ones, the Ludus Magnus, located near the Colosseum.

Gladiators underwent rigorous training, overseen by instructors called doctores, who were often former gladiators. Once a gladiator reached a sufficient skill level, his master would begin to rent him out for matches throughout the year.

Where Did Gladiators Fight?

Gladiator duels demanded a commanding stage, and nothing quite screamed “drama” like the Roman amphitheaters. At the height of the Roman Empire, there were more than 250 amphitheaters spread across the empire, however, none stood as formidable and dominant as the Colosseum. Originally holding upwards of 50,000 spectators, the Colosseum still stands as one of the most famous monuments from the ancient world.

Other places to see gladiators fight? If you were of a wealthy socio-economic status, you could host gladiatorial games in your home – or sometimes, Romans would also hold the games in public squares.

Fun Facts about Gladiators

Like the hand-to-hand combat sports you see today, gladiator fights involved a referee, a summa rudis, to ensure the match was fought fairly.

There were also many different types of gladiators – the Thracian, Samnite, Murmillo, and Retiarius – that were classified based on the weapons they used as well as their fighting techniques.

And did you know that some women fought as gladiators? While there were significantly fewer women gladiators compared to their male counterparts, there are historical records that indicate some women stepped up for these battles.

Other Roman Games & Sports

What else did the Romans enjoy watching when there weren’t any gladiators fighting on display? Read on to find out.

Pankration

Pankration, which translates to “all power” in Greek, was first introduced in 684 BCE. at the 33rd Olympic Games and eventually picked up popularity in Rome. Considered an intensive combat sport, Pankration involved recognizable elements of boxing and wrestling – with few restrictions and regulations for participants to adhere to.

Venatio

What happened when you dropped wild animals into an arena with other wild animals… or even men? The answer: a lot of people showing up to watch. This form of entertainment was called venatio, meaning “animal hunt.”

The “sport” gained so much popularity over time that wild animals from far and wide, such as lions, bears and crocodiles, were brought to Rome.

Support your local PBS station in our mission to inspire, enrich, and educate.

Chariot Racing

Before there was the Bugatti or Porsche to take for a spin around the race track, the Romans and Greeks had their own knack for speed. Enter: the horse and the charioteer.

The mechanics of chariot racing involved some challenging physics that often led to perilous outcomes. Charioteers would balance on a minuscule chariot while strapped to the reins of four to 12 horses. An average race consisted of seven laps around the stadium, a distance that stretched over four miles.

The races were exhilarating and sought-out spectacles… as were the crashes. If a charioteer lost his footing during a race, he would take out his dagger to cut himself free from his reins to avoid being trampled to death. Needless to say, it was a sport of high stakes and even higher thrills.

Ancient Roman Theater

When the Romans weren’t enraptured by their gladiator duels or chariot racing, they had the dramatic arts to turn to.

Influence From Greek Theater

Just like their fascination with Greek sports and athletics, the Romans took after their neighbors when it came to theater. By the time Athens lost the Peloponnesian War in the fifth century BCE., the state of Greek theater was on the decline. A more conservative social and political period elicited a widespread change to the art form, some of which were positive. Compared to prior centuries, actors had gained more new-found respect, were offered more acting opportunities, and had even started a guild.

However, for all of the improvements that came with the actors’ quality of life, the plays themselves underwent significant changes. For instance, acclaimed playwright, Aristophanes, who was known for writing lewd and pointed, political material, decided to tone back his criticism in response to the war. This choice is reflected in his famous play The Lysistrata which steers away from listing any politicians by name. From 400 BCE. to 323 BCE, the genre of Middle Comedy took centerstage, though no plays from this time survive today.

Following the short-lived middle comedy period, the Greeks beckoned in New Comedy. The plays from this new genre were notably less absurd and obscene than their predecessors. Contrasting with the tropes of Old Comedy, New Comedy plays did not mention phalli, padded buttocks, or gods and goddesses. Instead, these plays tended to focus on everyday people – fathers, sons, mothers, soldiers, and slaves – and their everyday stories. A writer largely attributed to the new comedy period was Menander, although despite writing more than 100 plays, only portions from four of his works exist today.

Roman Comedies

As Greece’s “Golden Age” of theater experienced its descent, Roman comedy began to find its footing. According to the ancient Roman historian Livy, the Roman theater evolved in five stages, beginning first with dances to flute music as well as “obscene” improvisational verses. One of the improvisational forms Livy observed was called the “Atellan farce.” This type of comedy drew on a kind of lewd miming that involved actors improvising various comedic scenarios based on stock characters.

At the same time that the Atellan farce picked up popularity, another form of comedy, Fescennine Verses, took hold among the people of Campania, a region in southern Italy surrounding the modern city of Naples. This comedy centered on actors delivering crude, jocular poems at harvest festivals. Over time, the Fescennine Verses melded with elements of dancing and song which produced a new form: the fabula satura.

However, it was the fabula palliata that proved to be pivotal. As mentioned earlier, the Romans were not shy when it came to embracing elements of Greek culture, and the fabula palliata did just that: it borrowed heavily from Greek originals, specifically the comedic works of Menander. These Roman comedies included outdoor urban settings and casts with stock characters. While all of these Roman comedies had people and settings with Greek names, the situations and jokes about current events were distinctly Roman.

Production of Roman plays versus Greek ones varied. Whereas the Greeks tended to associate the theater with a sense of civic duty, the Romans had government officials orchestrate the logistics of putting on a play. For instance, an aedile or praetor would oversee the drama festival and hire someone to produce the plays. This included locating costumes and masks, finding musicians, and hiring slaves and actors to act in the play. Unlike actors in post-classical Greece, Roman actors were not treated with any respect. In fact, Roman actors were not allowed to vote nor could they serve public office.

Check out this video essay from Crash Course Theater to discover more details about theater in ancient Rome.

The best of PBS, straight to your inbox.

Be the first to know about what to watch, exclusive previews, and updates from PBS.

Titus Maccius Plautus

One of the more well-known Roman comedy playwrights was Titus Maccius Plautus, born in 254 BCE in Umbria. Before taking up writing, Plautus worked as a stagehand and merchant, but he eventually made the move to Rome where he gained traction for his plays.

Plautus’s plays were known for their energetic and wild tones that often focused on stories about middle-class people and their slaves. His plays also experimented with meter, with many scholars believing actors delivered a majority of his writing as songs. His work went on to influence future writers, such as Molière and Shakespeare.

Publius Terentius

Perhaps one of the most remarkable playwrights to make his name in Roman theater was Publius Terentius, also known as “Terence.” He was born around 190 BCE in Carthage and was a slave owned by a Roman senator, a man who ultimately educated and freed Terence. Once freed, Terence traveled to Rome to take on his ambitions of becoming a playwright. In total, he wrote six plays, all of which were heavily influenced and borrowed from Menander. Upon embarking on a trip out to sea, his life came to a tragic end at the young age of 25.

Terence’s work is viewed as more sophisticated, though less outwardly funny compared to Plautus'. Additionally, his plays feature more suspense, fewer plot holes, and characters who are more grounded in reality.

Roman Influence Today

So the evidence is clear: the Romans knew how to entertain. Though, it’s probably for the best that few, if any, of their sports have survived to contemporary times.

Interested in more ancient history content? Stream "Julius Caesar: The Making of a Dictator" on PBS and check out our other great Roman history documentaries!