Representing Community and Culture

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in these stories are solely those of the authors.

For some Native Americans, the paths they have chosen in life - their profession, place of residence or daily rituals – actively reflect their heritage. Whether working as storytellers, passing traditions on to their children, creating art or raising awareness of Native American history and culture, these individuals continue their cultural traditions by sharing knowledge and creating space for Native American people in mainstream America.

Moon Flower (Mexica)

I'm a two spirit, spider woman kind of woman—I like to create and work with my hands. My childhood dream was to become an artist. I loved to bead, draw, paint, write, and be in nature, run in trails, climb trees, play with acorns. When I was around 16, I began learning the art of becoming a traditional healer and it's probably one of the oldest cultural traditions I've learned today, along with storytelling, poetry, song, drum and dance. I have been very fortunate to be guided and supported by my community in Indigenous arts and wellness, and one day hope to make an ancestral pilgrimage south to Mazatlán, Turtle Island.

Monica

I continue my cultural knowledge and traditions by integrating Endangered Language dialects into all of my personal projects as an XR Producer / Software Architect (VR, AR, MR and mobile software projects). Most of my projects are in the Indigenous Futurism genre and I'm grateful to have skills & resources to consider future possibilities where Indigenous languages, cultures and people can thrive while being respected and valued.

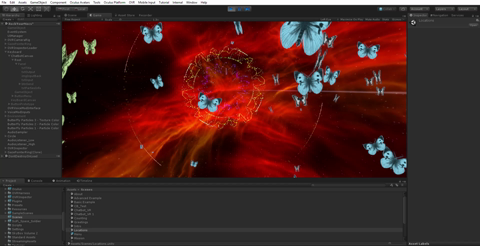

My current VR project 'iAmAi' looks at Ancient Intelligence vs. Artificial Intelligence while immersing people into a futuristic VR environment I am creating to let them see & hear Kanienkeha dialects.

I'm building 'iAmAi' for Oculus Go devices right now and will update it for Oculus Rift & Quest in spring 2019.

'iAmAi' VR Experience backstory of this VR experience:

You are on a massive outer space ship and the only human survivor. Many generations ago, your people left planet earth. You heard rumors that some of your people were left on planet Earth and they were Kanienkehake. You are hoping to learn Kanienkeha language so you can return to your Mother Earth, speak with your surviving people and maybe they will allow you to stay with them the rest of your days > instead of floating around alone on a weird spaceship.

Attached photo shows a scene I am working on now for an outer space 'Techno PowWow'.

Daazhraii

Part of continuing our cultural knowledge and traditions if finding ways to communicate it through different audiences and different mediums. Personally, I've always gravitated toward the arts - towards acting, poetry, and film. This photograph is a still from the stage of "Lear Khehkwaii" or Shakespeare's "King Lear". I played Cordelia and fellow actor, Allan Hayton, not only helped translate the script into our Gwich'in language - he also played King Lear. The play was set during the time that fur traders started to come into our traditional territories. We toured across the state of Alaska with this play and it was a profound experience to perform using our own Native language.

Kate (Ahdipiwin)

Damakota (I am Dakota) and mother to two young daughters. My husband is Oglala Lakota, and we try our best to share our language and traditions with our children everyday. As a public historian I work to elevate the stories and perspectives of my community and family in our ancestral homeland of Mni Sota. I am a citizen of the Flandreau Santee Sioux tribe, my ancestors were removed from the state of Minnesota in 1863, so I did not grow up in my homeland. Fifteen years ago my family returned home, and we are raising our children to know that they belong here and have a voice. We recently fought to have the name of the largest lake in Minneapolis (Lake Calhoun) restored to the Dakota name Bde Maka Ska (White Earth Lake) in honor of our grandparents who lived there.

Andi

As a Navajo person who did not grow up surrounded by cultural traditions, it's hard for me to say in what ways I continue cultural knowledge and traditions. One of the only times I remember taking part in any kind of ceremony was when my grandpa died almost two decades ago. My dad woke my sister and I up really early in the morning and we drove to my great-grandma's house. We had to wash our hair with yucca and listen to some prayers in Navajo. It was never really explained to us why we had to do this, it was just part of the grieving process.

Today, many people in the Navajo nation are connected very closely to their traditions. I see it every time I go home for weekend visits or summer celebrations. At flea markets I see corn pollen and things like sage and juniper, which are used for ceremonies. I hear rapid drum beats outside my parents' house when I visit sometimes because one of their neighbors makes hand drums and he's constantly testing them out.

As a Native journalist, I record contemporary Native stories and I see the great efforts Navajo people, and people from other tribes, do to strengthen and preserve cultural knowledge and traditions. I see individuals and whole tribes dedicated to keeping culture alive and it's reassuring to me to know that our culture is still a big part of our community.

Andi Murphy

Diné

Julianna

I try to continue my tribe's storytelling tradition - professionally through documentary film and personally, by sharing traditional stories with my young daughter. Storytelling is an oral tradition that has been passed down for hundreds and thousands of years and is used as a teaching tool to our young, for entertainment and for historical preservation. Before we had a written form of communication, we fostered a powerful oral tradition, and now that also includes modern-day techniques, such as film, poetry and photography, as well. The Comanche also created thousands of panels of rock art in Northern New Mexico that appear to tell stories of very important historical events to our people, perhaps some of the earliest examples of our storytelling tradition.