Season 14 of Call the Midwife brings us to 1970! I was thrilled to see the nurses and midwives convene and celebrate the joy and pride in achieving much-deserved pay raises.

I’m not sure why midwives are a branch of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) who always seem to be fighting for adequate compensation. We tend to fall behind our other APRN colleagues when it comes to salary, despite the critical role midwives play in the healthcare system and in improving outcomes for moms and babies.

The thing is, midwives can feel called to this work, and feel passionate about providing excellent, evidence-based care to our patients, and we are proud to be out here doing this work, but we also want and deserve to be paid adequately for our expertise. I have to admit, I got a little teary-eyed listening to the speech from this episode!

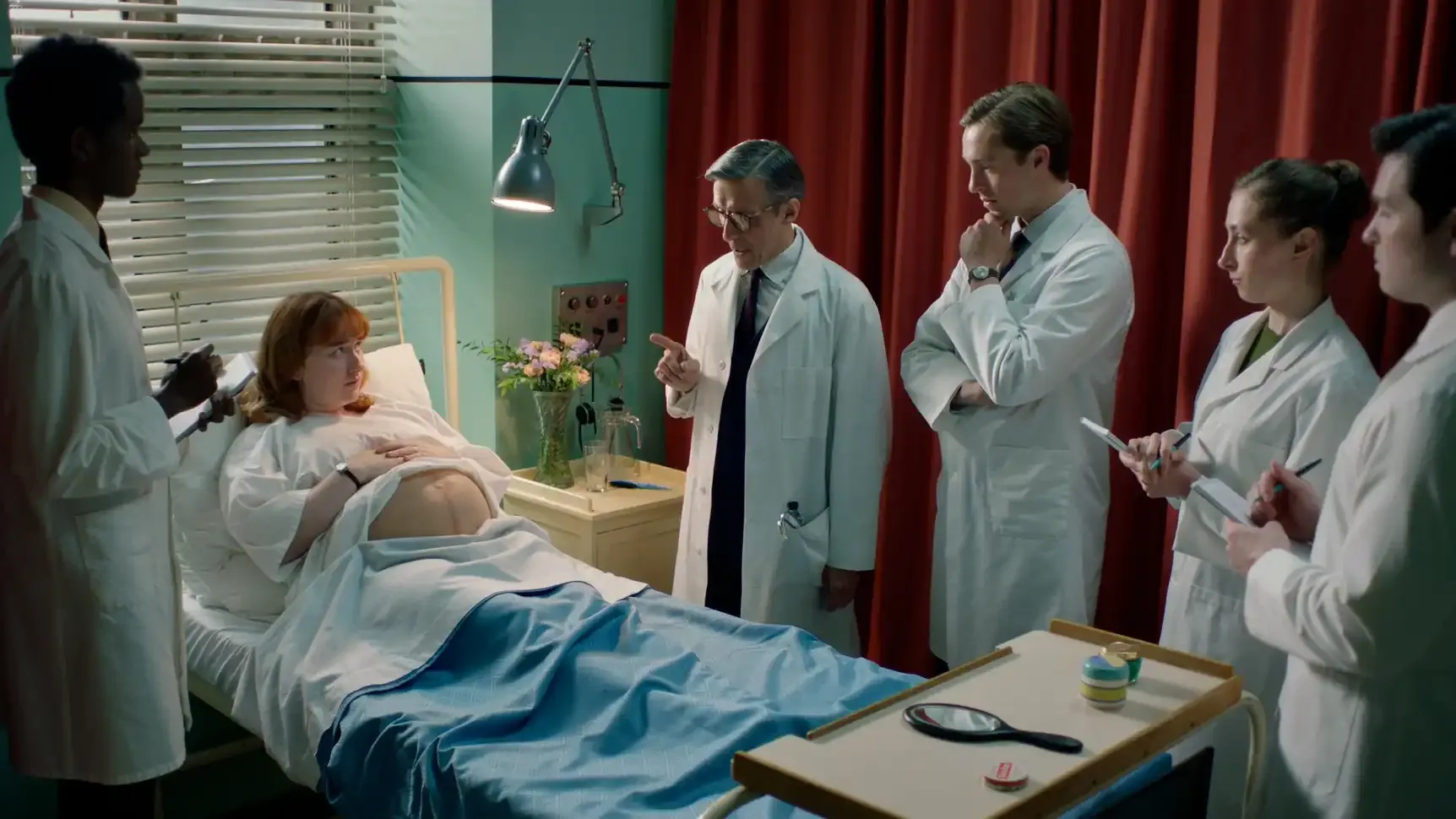

While that part of the episode felt near and dear to my heart, one thing that will never stop feeling wrong is watching the team of doctors and students at St. Cuthbert’s Hospital round on the patients. They never fail to talk about the woman like she isn’t even there, and their responses when she does try to interject are always rude and condescending.

My hospital recently started “multidisciplinary rounding” on both day and night shifts, where the team of physicians, midwives, the charge nurse, and the patient’s nurse round on every laboring patient or high-risk patient on the unit. We do this so that each patient can meet the entire team for that shift. We do this as a means of both keeping all of the staff aware of what is going on with our patients but also so that patients know who we are if we end up involved in their care during that shift.

It’s never fun to meet someone for the first time when you’re half-naked and a baby is coming out of you! We are very careful to make sure that everyone knows what the care plan is for that shift, but we aren’t just talking about the patient right in front of them. We are introducing ourselves, answering questions, and reviewing the patient’s birth plan/preferences so that everyone will be on the same page. I promise you; it is a much more pleasant interaction than the rounding we see back in the 1960s and 70s at St. Cuthbert’s!

One of these unfortunate rounds involves Winnie Welch, who was being seen for an appointment at St. Cuthbert’s because she is pregnant with her second baby, and she had her first baby via a cesarean section. We learned that Winnie had gestational diabetes in her first pregnancy, and her baby was over 10 pounds. We also learned that she had a classical incision on the uterus, meaning a vertical incision in the upper part of the uterus.

Today, we most commonly use a transverse (horizontal) incision in the lower uterine segment when performing a cesarean, and a double layer of stitches is also used when closing the uterus after the baby is delivered. This type of incision, in the lower part of the uterus, makes a uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies less likely to happen.

For women with one previous low transverse incision, and adequate time for healing (spacing the next pregnancy at least 18 months after the previous c-section), the risk of uterine rupture is less than 1%. For a previous classical incision, the risk of uterine rupture is between 4-9%.

While the doctors were rounding on Winnie, they never once answered her questions directly or explained what their rationale was recommending a repeat cesarean section. Winnie ended up doing research on her own, which led her to a medical text that showed an illustration of a uterine rupture.

Winnie had initially been upset that they wouldn’t entertain the idea of a vaginal birth after her cesarean. Then, she also felt blindsided by this risk of uterine rupture, which at that time, would likely mean death for the mother and the baby.

I was so grateful for Dr. Turner, Phyllis, and Rosalind for taking the time to educate Winnie and explain the reasons for their recommendations. They didn’t disagree with the doctor from St. Cuthbert’s, but they were able to present the information in a way that Winnie understood so she could make the best decision for herself.

I have been a midwife now for 13 years, present at around a thousand births, and I have seen uterine ruptures. I am grateful that my experiences have mostly been very different than Nurse Crane’s. A big part of that difference is that I attend births in a hospital that has surgical staff and providers present around the clock, and we utilize continuous external fetal monitoring for everyone undergoing labor after a previous c-section.

This is the current standard of care for people who would like to labor after a previous c-section. While we know that continuous fetal monitoring is not proven to improve outcomes in healthy, low-risk pregnancies and labors, it does improve outcomes in higher risk situations, such as a TOLAC (trial of labor after cesarean).

Sometimes, we will notice subtle, concerning changes in the baby’s heart rate prior to a full uterine rupture, or we might see something called a “window” at the time of a repeat c-section.

A window is pretty much what it sounds like – the uterine muscle can thin out so much that we can see through it. If left to labor much longer, a window would likely turn into a uterine rupture.

Sometimes, we will see the heart rate changes and quickly react by performing a repeat c-section, and we will find a uterine rupture. Other times, we see the baby’s heart rate changes, and perform a c-section, but we don’t actually see a rupture or any known reason for why the baby’s heart rate had been dropping.

For Winnie, she felt certain that she wanted the repeat c-section after learning about her risk for uterine rupture. However, her baby had different plans! When she was not able to make it to the hospital due to protests blocking the streets, she had Phyllis and Rosalind there to guide her through.

I can imagine what was going through both of their minds. I have experienced traumatic, tragic outcomes for moms and babies. When this happens, it is very hard to not overreact to every situation that reminds you of that one terrible event.

I can put myself in Phyllis’ place as she struggled to even care for Winnie, since she was so focused on needing to get to the hospital immediately. I have also been in Rosalind’s place. I have been in a situation that is far from ideal and a little scary, but you have to do what you can to keep everyone calm and still provide the best care possible.

Rosalind was able to keep Winnie calm, while still working hard to get her the care she might need (delegating Phyllis to call for an ambulance, and Winnie’s husband to get the boiling water ready), preparing for the imminent birth, and help work through both Winnie’s and Phyllis’ fears. She knew that a uterine rupture could happen. But she also knew she had no choice but to care for Winnie and felt that keeping her calm and helping her feel safe and cared for would also greatly impact how this birth would unfold.

Fear and adrenaline can impact oxytocin release, which impacts labor. We also know that fear increases pain perception.

I loved seeing Rosalind encourage slow, deep breaths, and she kept her voice calm and low, but firm. Although she was likely very anxious on the inside, she kept her outer appearance calm and collected. In the end, I’m so grateful that Winnie ended up with a safe, healthy birth.

The support and shared decision-making that midwives are known for, combined with our expertise, can improve outcomes for so many vulnerable populations. A great example of this was seen when Joyce was chosen to care for Paula Cunningham.

Paula is a 13-year-old girl who comes from a very religious family, and she doesn’t have a lot of understanding about her own body, the changes of puberty, or how babies are made. Her mother hadn’t wanted her to go through the sexual education courses at school, because she felt it wasn’t appropriate for a child to learn.

However, much as we know today, sex ed does not encourage promiscuity. In fact, it helps teens and adolescents know more about what is going on with their bodies and make safer choices.

Unfortunately, Paula and her family had to deal with the consequences of her unintended pregnancy. The saddest part for me was Paula not even realizing that she had partaken in anything that was risky or wrong. Because she didn’t know what sexual intercourse was, or how babies were made, she had no understanding that the “games” she was playing with her friend could result in a pregnancy.

Paula came from a loving family. Winnie did as well. The midwives love their jobs, but it is also stressful and demanding work.

Love is necessary, but it will only get you so far. You still need education, housing, food, and transportation. You need access to healthcare. So, on this one, I have to agree with Rosalind that while the sentiment of the Beatles’ hit is quite nice, it’s not exactly true.

This episode's themes of social unrest, complex maternal health, and the delicate balance between honoring someone’s faith and accepting science are challenges we are still facing today. Call the Midwife always seems to emphasize the compassionate, patient-centered care that midwives are known for, while also showing how midwives regularly adapt to societal and cultural changes as well as evolving medical practices.